Chicago's new mayor

The fiscal realities facing the nation's third largest city will require innovative solutions to solve its serious social ills.

The city I call home has long pioneered innovative solutions to alleviating poverty.

Brandon Johnson, Chicago’s next mayor, gave a shout-out to that tradition in his victory speech this past week when he mentioned the founder of Hull House, who in 1889 launched the settlement house movement to bring art, culture and education along with basic social services to the city’s impoverished neighborhoods. “The legendary Jane Addams taught us to educate the whole child,” the middle school teacher and teachers union organizer-turned-politician said.

During the heated campaign between Johnson and Paul Vallas, a former city school superintendent backed by the Fraternal Order of Police, both candidates focused on the city’s recent uptick in crime, which every poll said was the number one issue on voters’ minds. Their competing visions for how to reduce crime dominated their well-funded advertising campaigns.

Vallas promised to hire more uniformed officers and implement more aggressive street-level policing. In other words, the losing candidate proposed ramping up the anti-crime strategy that has dominated urban policy for over half a century and created the largest prison population on earth. That approach had little demonstrable effect on the ebb and flow of national crime rates, which, until the pandemic, had been on a decades-long decline with only a minor reduction in the nation’s prison population.

Johnson, who was backed by the teachers and most other public employee unions, offered a direct challenge to that approach even as he backed away from the “defund the police” rhetoric of some of his supporters. He promised to invest more city resources in education, housing, youth employment and mental health. He proposed a direct assault on root causes of crime — the social conditions that lead many youths, especially in poorer minority neighborhoods, to join criminal gangs trafficking in illegal guns and drugs.

“We don’t have to choose between toughness and compassion; between caring for our neighbors and keeping ourselves safe,” Johnson said in his victory speech. “Those false choices do not serve our city any longer.”

That debate has its analog in health care. Poor people and workers in the bottom half of the income distribution, stripped of the union protections that once provided the working class with a decent standard of living, suffer far more than the middle class from ill-health. Their lives are plagued by life-shortening conditions like heart disease, cancer, diabetes, substance abuse and mental illness. The life expectancy in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods lags 15 years behind the richest precincts in and around the Loop. Their residents are more likely to consume expensive health care through government programs, which crowds out spending on other social services that could help them avoid getting sick in the first place.

U.S. — an outlier nation

This is a national problem, one that affects every impoverished area whether in large cities, rural areas, deindustrialized towns and small cities, or the hills of Appalachia. If you look at the share of the U.S. economy devoted to public and private spending on health care and social services, it is not much different from what most countries in western Europe or Japan spend combined on those categories.

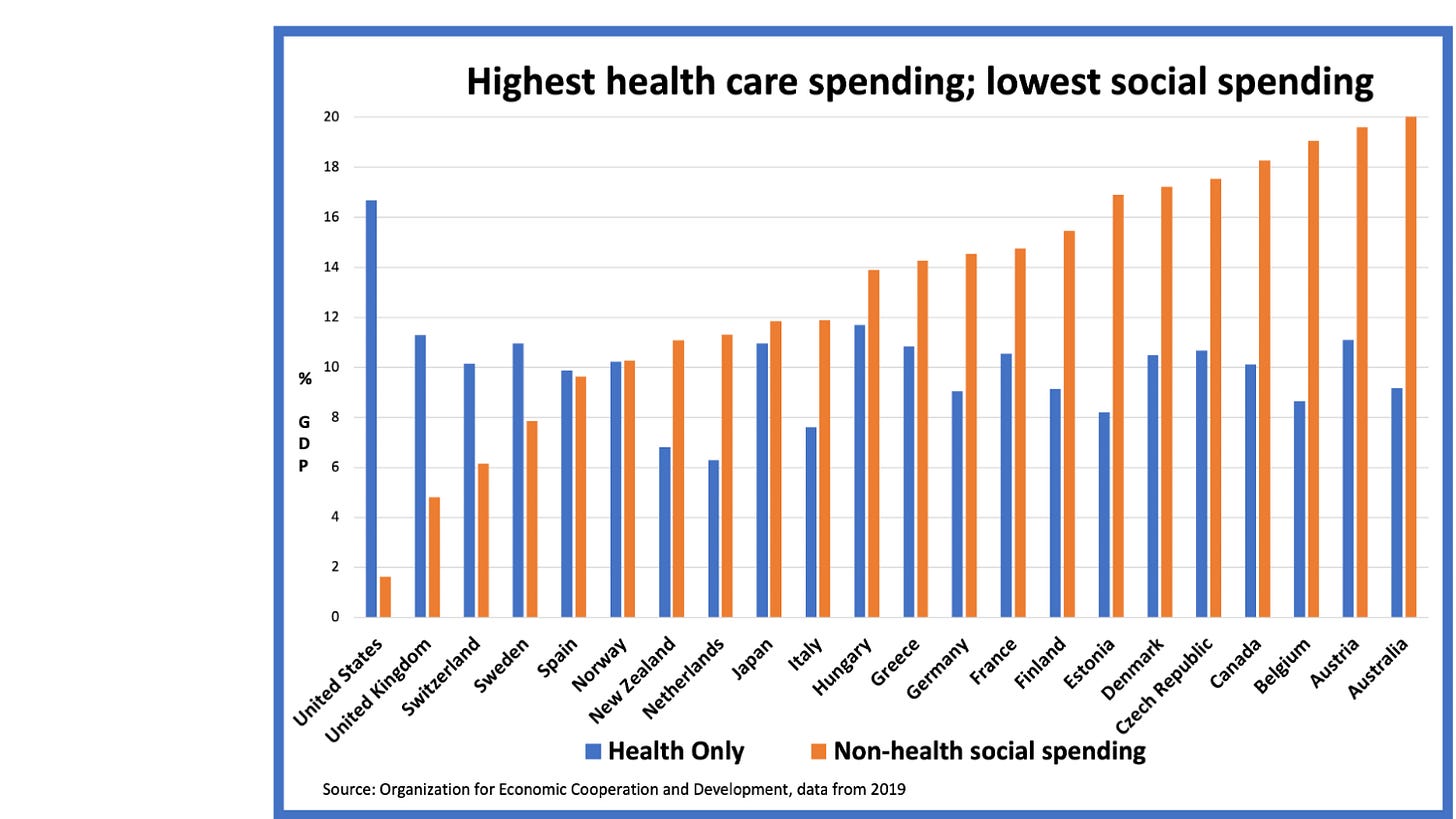

The big difference is that the U.S. spends 90% of its combined health care/social service budget on its high-priced health care system, and just 10% on social services. Most countries take an opposite approach, often spending significantly more on social services than they do on health care, as this chart shows.

What does the OECD include in its calculations of non-health social spending? Housing assistance. Food subsidies. Job training. Income support. Child care. Early childhood education. Environmental clean-up. In the U.S., these programs received a boost in the 1960s and 1970s. But in the four decades since, there has been a steady retreat in the use of federal funding to support families and alleviate poverty.

The U.S. social safety net, even in the heyday of the war on poverty, was never very good. Today, it is a pale of shadow of its initial inadequate incarnation.

Incoming Mayor Johnson will quickly discover that fact as he tries to achieve his laudible goals while balancing his first city budget. Unlike the federal government, cities and states must balance their budgets. This year, the city will lose a substantial share of its emergency pandemic funding, most of which went for maintaining or expanding community services like public health and housing assistance and providing recessionary budget relief.

The state, like the rest of the country, will also see fewer people with health insurance after the emergency rule dropping the annual review for Medicaid eligibility falls by the wayside. The federal government estimates 700,000 low-income Illinois residents will lose Medicaid coverage this year, about 18% of people in the program. State officials suggest it will only be half that amount through its efforts to re-enroll those still eligible for Medicaid or get them enrolled in Obamacare plans. That would still be a sharp blow to the health and well-being of Chicago, where about a third of state Medicaid enrollees live.

Some new spending coming

On a positive note, the city over the next several years will receive a substantial boost in funding from the bipartisan infrastructure law and Democratic Party-backed Inflation Control Act, which included major new investments to boost clean energy and combat global warming. But those programs will provide minimal support for the kind of education, job training and economic development programs Johnson wants and the city desperately needs.

He'll find little wiggle room in the share of the city budget raised from local taxes. Nearly 60% of the city’s $5 billion corporate fund pays for its 34,000 workers and retiree pensions. Pension contributions are slated to rise dramatically over the next half decade to redress years of underfunding by previous city administrations. Direct spending on public safety (police, fire, and related agencies) absorbs 45% of the corporate fund. Local funding for community and social services, most of which subsist on federal grants, is less than 4%.

To put that another way, unless Johnson defunds the police or raises taxes, there’s no way he can generate money for investing in new programs. The city needs outside help.

Unfortunately, little will be coming from the state, which faces its own pension problems. A constitutional amendment to allow a graduated income tax (it is currently just under 5% for individuals and doesn’t tax retiree income) was decisively rejected by voters in 2020, falling 15 percentage points below the 60% needed for passage. A massive lobbying blitz led by its wealthiest private equity and hedge fund owners, including Citadel’s Ken Griffin, doomed the initiative.

After the vote, Griffin and his corporate headquarters decamped to Florida after complaining about crime in Chicago. “Taxes weren’t part of our decision to come to Florida,” he told the Republican mayor of Miami, the largest city in a state that has no income tax.

During his campaign, Johnson proposed a budget that embraced Griffin’s words, if not his actions. He outlined a series of business tax increases on employers, financial transactions, hotel stays, and high-end real estate transfers to pay down pension debt and increase spending on social services.

That budget, once introduced in the 50-member City Council, is certain to draw vehement opposition from the local business community. While the city’s corporate elite give verbal support to tackling the social determinants of health and crime, they overwhelmingly backed Vallas. They also have substantial support on the council, where the large and growing progressive caucus is still below a majority.

Given the fiscal constraints, the novice Johnson administration, like Janes Addams more than a century ago, will need to find innovative approaches locally for redressing the social ills that continue to plague communities marred by entrenched poverty and low-wage work. They are out there. I’ll take a look at a few in my next post.

Thank you once again for an excellent article on Chicago’s choices and efforts to increase social investment.

It seems Chicago’s dilemma is a core American problem. The anomaly is electing a courageous mayor willing to open the discussion of American priorities.

You highlight the history of ignoring the social determinants of health and crime. The ability of wealthy oligarchs to control politics to assure austerity funding for social investment, while fighting any taxation which might threaten their wealth, privilege, or impunity while directing funding to the mechanisms of social control: surveillance, increasingly militarized policing, and massive incarceration.

This is not a system designed to assure the wellbeing of the whole public. It is a system of Social Murder.

It is a system designed explicitly to avoid investing in the social determinants of health and crime which guarantees health, education, social harms including unnecessary suffering and death to whole segments of society. Not coincidentally, poor, vulnerable, and people of color.

Unless this reality is called out, I fear the new mayor will continue to struggle in a system heavily rigged against the people. He may gain small concessions, but that is the well worn strategy of cooption.

It is time for Chicagoans to be offered a real choice: the status quo of Social Murder, or a real change to a society build on Social Benefit. Benefit the few, or the many?

We are at the proverbial Einstein insanity moment: Continuing to do what is not working expecting different results. Or change our paradigm to benefit society as a whole first. Start by investing in the social determinants of health and crime. We can do better.

Most of the analyses of social versus health spending are not very good.

U.S. problem is that health spending does crowd out everything else.

It's five times our defense spending, something that 10 out of 9 health care reporters don't know.

And we're not talking only about high health spending on low-income people. It's high health spending on most of us who actually get care.

The cause of this problem is simple ANARCHY in health care. Anarchy is what we are left with when we don't have either a competitive free market in health care (unattainable) or competent government action in health care.

No one in U.S. health care is accountable for anything that happens outside the building where they work. Only one state even has a list of the ERs and hospitals needed to care for people who are sick or injured. And no entity is accountable for doing anything real to address the primary care crisis, the LTC crisis, the soaring out-of-pocket crisis, or any of the others.

The $4.7 trillion we will, together, spend on health care should make it the easiest problem to solve in the U.S.

But let's not pretend that better prevention will cut health costs. We should prevent all the illnesses and injuries we can. But prevention has a 100 percent failure rate. That's when we need medical security for all Americans--confidence we'll get effective, quick, and kind care without any worry about the bill.

Focusing on the "social determinants of life" today just let's health care off the hook.

With half of health spending wasted, and with health care sponging up an added $200-$250 billion each year, we'll never have money to address social determinants until we get health care costs under control.