The ethics of an early end to vaccine trials

The continuing good news on COVID-19 vaccine efficacy suggests the outcome of the upcoming December 10 meeting of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee is a foregone conclusion.

Unless something is horribly amiss with their data, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine will get the committee’s blessing; the FDA will quickly give it Emergency Use Authorization (EUA); and the government will launch rapid distribution of the vaccine to the American people. The Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines will probably get similar quick go-aheads.

There can be no doubt about the ethical obligations of COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers under these circumstances. Clinical trial participants in the placebo arms of the trials will be offered access to the real thing and, I suspect, most will take it.

I say this because volunteers receive that promise when they sign the informed consent agreements required for participating in the trials. Trial organizers offer those terms not only because it is ethical, but because it makes it easier to sign up volunteers.

Unfortunately, an early end to the placebo arm in the trials may eliminate the public’s ability to learn crucial information about the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness. They include the possibility of rare but serious side effects; the vaccines’ usefulness to different segments of the population; and how long immunity lasts.

These issues need to be thoroughly explored by the advisory committee. The FDA should also ask its advisors to offer potential alternatives for obtaining valid data on those issues, so necessary to convincing hundreds of millions of people to get their shots.

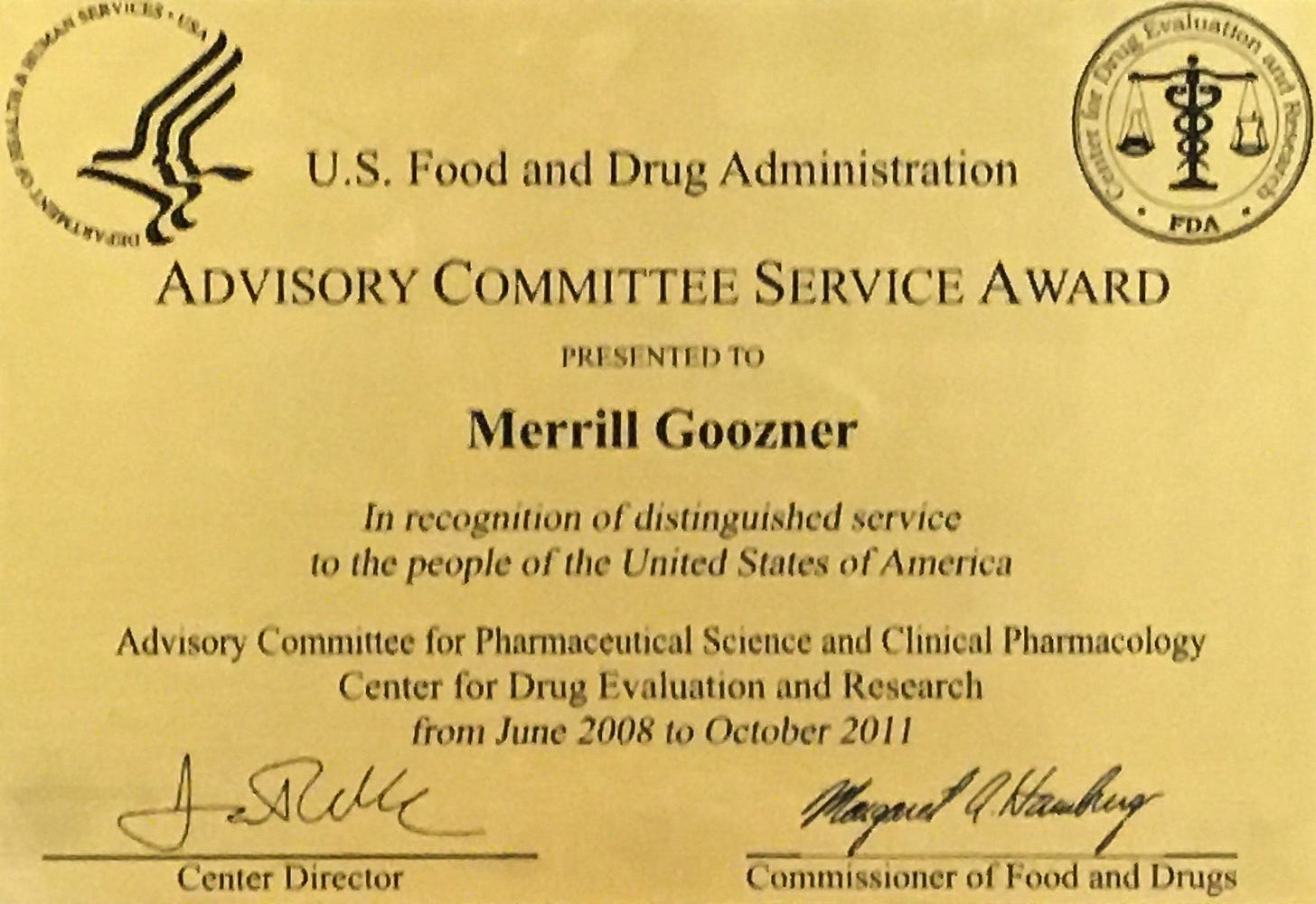

If I were sitting on the advisory committee, here’s some of the questions I’d be asking: (As the above certificate attests, from 2008-2011, I served as the consumer representative on the FDA’s Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Pharmacology Committee; I also sat on a number of disease-specific committees evaluating new drugs.)

How will shutting down the placebo arm affect our ability to learn whether it may be associated with rare but serious adverse events?

The original trial protocols called for collecting incidents of serious adverse events (SAEs) for at least six months after administration of the second dose in at least 6,000 people in the trial. SAEs are things like seizures or life-threatening allergic reactions, not the mild and temporary redness, sore muscles or fatigue that sometimes accompany vaccination.

The trial began near the end of July. Even if we assume the dozens of trial sites signed up 6,000 people on day one, the second dose wouldn’t have been administered until the end of August. Six months beyond that is the end of February. If the comparison arm is unblinded and given vaccines prior to that date, how will statisticians determine if the limited number of SAEs, if any, were caused by the vaccine or were simply random? A comparison arm is needed to determine that.

A statistically valid identification of a rare SAE doesn’t preclude approval. Given the huge medical and economic benefits from a highly efficacious COVID-19 vaccine, a certain amount of risk is certainly worth taking. Quantifying that risk, especially when it is small, will encourage people to take it — not the opposite. It will give health officials data to confront the vaccine skeptics.

How will eliminating the placebo arm affect our understanding of how long immunity lasts?

This is an especially relevant question for vaccines that appear to be 90% or more effective. Infection rates may begin rising again, including among those who’ve been vaccinated, near the end of the original one-year trial period.

That may happen for a variety of reasons. There may be an upward tick in infections in the general population due to the gradual rollout of the vaccine amid a relaxation of masking and social distancing. Or it might be due to widespread failure to take the vaccine. Or it might be due viral mutations. Or it might be a combination of factors. Again, eliminating the placebo arm before the full year in the original trial protocols precludes getting a definitive answer to whether annual vaccines will be necessary.

How will unblinding the trial and giving everyone the vaccine affect what we know about how much it helps different groups?

The Pfizer/BioNTech trial’s inclusion criteria segregated volunteers into three major groups: children 12 and under; adults between 18 and 55; and seniors 65 to 85. All the companies pursuing vaccines also pledged adequate representation of minorities in their trials.

Yet Moderna announced in October (https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/10/22/vaccine-trial-moderna/) that just 20% of 30,000 enrollees were Hispanic and 10% were Black. Pfizer had an even lower rate – estimated at under 30% for both groups, according to early October news reports. The latest data from the CDC show 25% of the nation’s cases were among Hispanics and 15% of cases were among Blacks.

Will the vaccines provide the same level of immunity in those communities, which are suffering disproportionately from the disease? Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to live in crowded conditions; more likely to work in at-risk occupations; and more likely to suffer from other, serious health conditions compared to white communities. Similar questions apply to seniors, the very young or people with specific health co-morbidities like diabetes or heart conditions.

And, as looks increasingly likely, there are going to be multiple vaccine options. Rigorous subgroup analysis will let clinicians and the public know if one works better than another among different subgroups.

Maintaining a comparison arm for each of these subgroups long enough to provide clinicians and public health officials with statistically valid differences in efficacy would provide important insights into what vaccine to take and what additional measures may be needed to halt disease transmission in the most adversely affected communities.

It’s an opportunity, not a roadblock

I raise none of these questions as potential roadblocks to giving these vaccines EUAs (assuming, of course, the submitted data is as conclusive as the data contained in the companies’ press releases). Rather, the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and their advisory committees need to recognize that ending the placebo arms in the trials will leave many questions unanswered.

In the few weeks left before the meetings, officials should develop proposals for alternative approaches to collecting data for when companies assert their ethical need to abandon the gold standard of a randomized clinical trial. They include a much-improved system for collecting reports on serious adverse events; requiring public health authorities and health care providers to gather accurate data on when new cases arise in people who’ve been vaccinated; and better reporting on the causes of outbreaks in minority communities, nursing homes and national hotspots. The advisory committees should be asked to make recommendations on those proposals.

The ability of industry and government-funded scientists to deliver a vaccine within a year of the emergence of a pandemic-causing pathogen is nothing short of a miracle. But vaccination rates in the U.S. have been declining for several decades, in part because of widespread disinformation about their safety and efficacy.

It’s time to apply the same scientific rigor to collecting data after the vaccines’ deployment as was applied to their creation. If people knew such data collection systems were in place, it would go a long way toward ensuring the new vaccines are trusted and taken.