Food inflation and insecurity

More than a quarter of the food produced in the U.S. goes to waste. Cities should recycle it to feed the hungry.

The airwaves and email inboxes will be flooded with post-debate punditry tomorrow. So let’s talk today about some news that will be drowned out by the noise. The Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its monthly report on inflation on Wednesday morning.

If the top line number is around 2%, which is the Federal Reserve Board’s target, markets will rally. Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues will be empowered to move forward with plans to lower interest rates, perhaps by a half point, when it meets on Sept. 16-17. He signaled a decrease was coming during the annual international banking conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in August. The only question was its size.

The Harris campaign will no doubt cheer a move that should give the slowing job market and housing market a boost. They will do it quietly, though. These days it is only Democrats that honor the long-standing principle of Fed independence.

I suspect the Republican candidate will use his social media platform to attack the Fed for trying to influence the election. He might even withdraw his hedged promise that, if elected, he will allow Powell to serve out his term, which ends in 2026. Trump told Bloomberg News two months ago that “I would let him serve it out, especially if I thought he was doing the right thing.”

The one thing a low number won’t change is negative perceptions about the economy, which have been largely driven by concerns about inflation. Although a return to normal inflation will be good for jobs and housing markets, millions of American are still feeling the pinch from the COVID-driven spike in prices, especially when it comes to food.

Sticky food prices

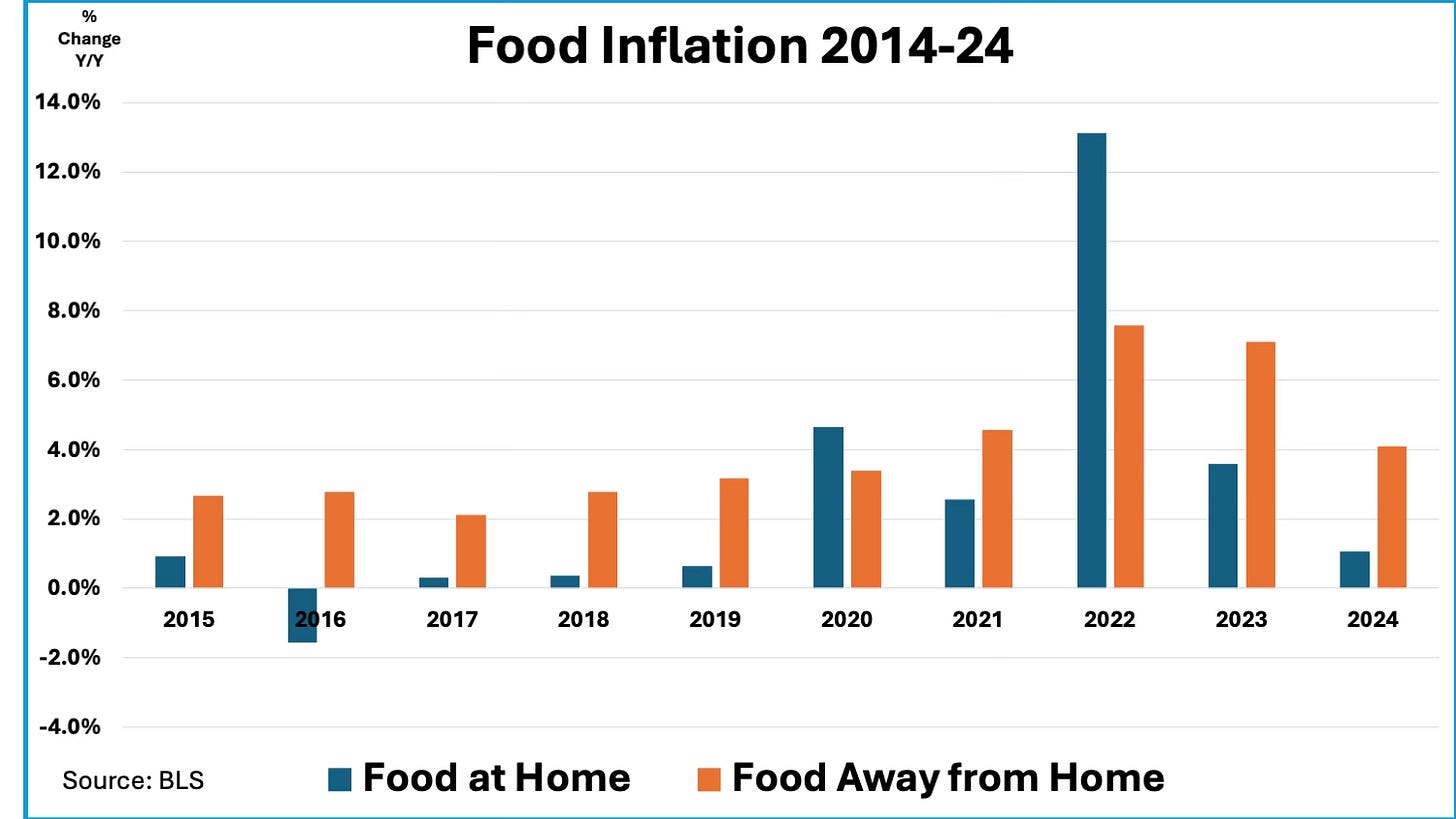

What goes up almost never comes down. Nowhere is that more acutely felt than in food prices. You can show people that the price of a dozen eggs or a box of breakfast cereal is now holding steady. But that doesn’t erase the fact they are up 42% and 20%, respectively, from where they were in 2021 before the COVID-related supply chain shock hit home.

That is like levying a huge tax on the household budgets of low-and-moderate income families, who spend a larger share of their income on food. A new report on food insecurity from the U.S. Department of Agriculture released earlier this month found that 13.5% of households struggled to afford groceries in 2023, up from 10.2% in 2021.

The increase was driven higher prices for basic foodstuffs. President Biden’s decision to end the COVID emergency made things worse because it put a halt to increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance and a more generous free-and-reduced school meal program.

There’s also been a change in the zeitgeist. During the pandemic, many schools, even if they were shut down, kept their kitchens open to provide free meals for pickup. Many low-and-moderate income families were able to afford the higher food prices because their paychecks were protected. Plus, they received a larger child tax credit. Some received help from their local communities. Donations to food banks surged.

But now all that’s gone. As those extra benefits efforts waned, food insecurity rose to levels not seen since the financial crisis era of 2008-2014.

What is food insecurity? Here’s how Oklahoma State University sociologist Michael Long and Ph.D. candidate Lara Gonçalves, who study the phenomenon, described it in an article on The Conversation website:

“If you can’t afford to refill the fridge, find keeping a balanced diet too expensive, eat too-small portions, skip meals altogether, experience the physical sensation of hunger or lose weight solely due to lacking the money to put food on the table, you’re experiencing food insecurity.”

Long and Gonçalves believe food insecurity will continue to rise for at least the next year. “Barring any major policy changes that continue to slow inflation and dramatically reduce the price of food in 2024 or 2025, this rate is unlikely to drop again in the Biden administration’s final year or the first year of the next president’s term,” they wrote.

Read more GoozNews coverage of An Agenda for Ending Food Insecurity here.

Waste not, want not

It’s sad that people have to go hungry in the country that has the most productive agriculture sector in the world. It’s maddening when you realize that anywhere from a third to 40% of what our farmers and food processors produce goes to waste.

There’s waste at the factories where farm products are processed and packaged for grocery store shelves. There’s waste when food processors throw away produce because of minor flaws or being the wrong size for packaging. There’s waste at grocery stores when unsold goods with expired sell-by dates are thrown out. There’s waste at home when stale and expired groceries or half-eaten meals are thrown in the garbage.

Where does most of it go? To landfills, where it rots, fouls the air and generates methane, which is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Landfills are the third largest source of methane gas emissions. Fully a quarter of landfill emissions come from food waste. The United Nations Environment Program estimates 8% to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions come from unconsumed food.

This wasted food represents an extraordinary opportunity. Why not turn it into a usable product, one that not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions but helps feed the hungry?

That’s exactly what is taking place in a number of communities nationwide. I was fascinated to read over the weekend about one program on Chicago’s South Side, where food scraps gathered from city composting sites will be used to fertilize an urban high-rise farm factory producing vegetables for a part of the city that has been abandoned by major grocery store chains.

It’s founder, Erika Allen, who grew up on a farm in South Carolina, created the Urban Growers Collective in 2017 to promote urban agriculture. She has since raised $35 million to build an anaerobic digester for turning food waste gathered from collection sites and landfills into compost. She plans to use that compost on a vertical farm for growing vegetables, which will open in 2027. An education center on the site will also include a store where local shoppers can purchase fresh produce.

“The fact that we have all this food waste is obscene, but we’re going to always have it because we eat and we’re humans,” Allen told Block Club Chicago, a start-up news site that features local news. “If we’re going to have surplus, it should go to facilities like this. We’re transforming and greening the community and making this a climate hug.”

I hope to visit soon to learn more about this project. It sounds like one of those ideas that ought to be scalable. I’ll report back when I do.