Health care at risk

As Dems open their convention, the stakes in this year's election couldn't be higher. Access to reproductive rights, lower drug prices and affordable insurance hinge on the outcome.

Tonight’s opening of the Democratic National Convention will pay tribute to outgoing President Joe Biden. When it comes to health care, he has a lot to be proud of.

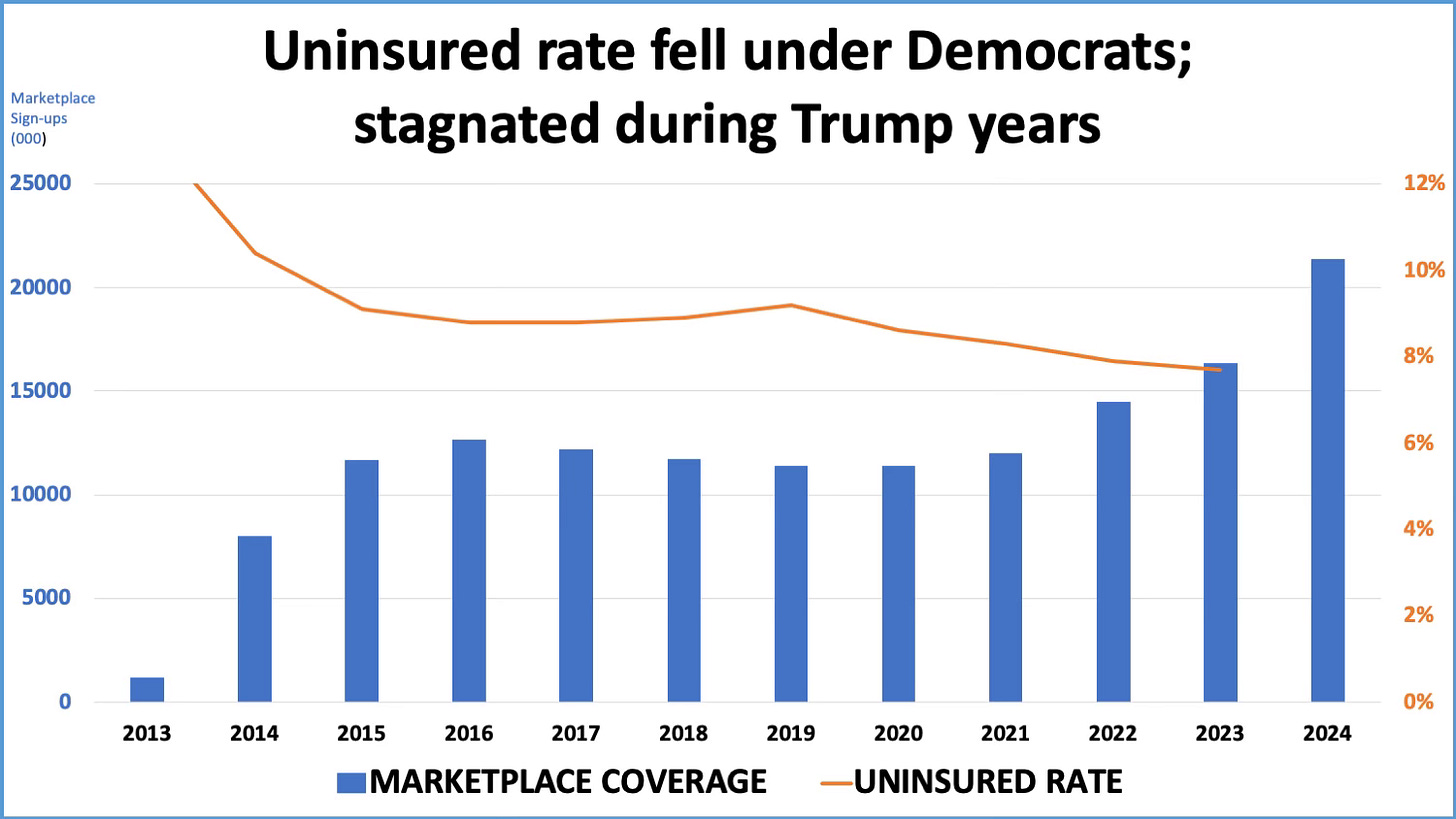

During his four years in office, the uninsured rate fell to the lowest level in U.S. history (7.7% last year). The number of states still refusing to expand Medicaid fell to ten after purplish North Carolina and deep red South Dakota joined the parade and raised they're income limits for entry into the program.

While the uninsured rate rose to 8.2% in the first quarter of this year — largely due to the reinstatement of annual Medicaid redeterminations with the ending of the COVID emergency — it is still below the nearly 9% uninsured rate under the previous president, where it had stagnated during his four years in office.

How did Biden manage that? The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act sharply increased subsidies for Obamacare plans, which made their premiums much more affordable for low-and-moderate income families. As a result, a record 21.4 million household signed up for plans this year. Moreover, he ended the Trump administration’s policies of refusing to help people sign up for plans or advertise their availability.

The administration’s IRA also gave the government the right to negotiate drug prices. While it only covers 10 drugs and doesn’t go into effect until 2026, it is the proverbial start. The number will grow to a cumulative 80 drugs by 2030, saving taxpayers an estimated $25 billion through 2031.

But that’s not its most important savings for drug consumers. As this New York Times op-ed today by Dr. Aaron Carroll reminds us, the IRA also caps out-of-pocket drug spending for everyone enrolled in Medicare at $2,000 a year starting next year. This is, as someone with orange hair likes to say, huge.

The insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers selling Part D drug coverage are the direct beneficiaries of the negotiated lower prices. Seniors only benefit to the extent those companies pass the savings along. The $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket expenses, on the other hand, is an insurance regulation that requires all but $2,000 gets paid by those insurers. More importantly, the cap applies to all drugs, not just those whose prices were negotiated in this or future years.

For example, if you take Jardiance for diabetes, the price CMS just negotiated with Eli Lilly reduced its cost by $376 to $197 a month. Even if your insurer passes that entire cost along to you in the form of a co-pay (unlikely in most cases), you would be done paying for the drug after ten months. For a cancer drug like Imbruvica, which price dropped over $5,600 a month to $9,139, you’d never pay more than $2,000, almost all of which would come in the first month of treatment.

The one issue where Biden can’t claim any victories is reproductive rights and abortion access, which has been severely limited in dozens of states after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. But that outcome was the result of Donald Trump’s Supreme Court appointments, who, contrary to their Senate testimony when nominated, put their ideological and religious beliefs ahead of legal precedent and a woman’s right to choose.

That issue will be highlighted tonight during the convention’s opening session when three women will talk about their experiences being denied medically necessary abortions because of the Dobbs decision. Trump says he is proud of his appointees; proud of the Dobbs decision; and would leave up to the states to decide if women should be prosecuted when they violate abortion restrictions.

Where they stand

It’s crystal clear where both candidates stand on these three major issues. Democratic soon-to-be nominee Kamala Harris will fight to maintain the increased subsidies for Obamacare plans when they come up for renewal next year. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis estimated annual out-of-pocket payments for Obamacare plans could double without the enhanced subsidies.

Republican nominee Trump will eliminate the added subsidies to help pay for extending his 2017 tax breaks, which went almost entirely to corporations and wealthy individuals. Those tax breaks also come up for renewal next year.

Republicans in Congress are already setting the stage for a big fight next year over repeal, claiming people or the brokers that sign people up for plans have deliberately misstated their incomes to qualify for higher subsidies. But as this recent news account points out: “Those who incorrectly project their incomes -- possibly because they work irregular retail hours, are self-employed and give a best guess of business, or get an unexpected raise or a new job -- must pay back all or part of the subsidy.”

A Republican Congress could also put limits or eliminate the government’s new drug price negotiating authority. Even if it remains law, a different set of appointees at the Health and Human Services department could choose to cut sweetheart deals with drug manufacturers. Trump’s HHS secretary was a former Eli Lilly executive.

When it comes to reproductive health rights, Harris has vowed to introduce legislation that would codify the right to abortion as defined by Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that protected that right up to fetal viability (about 26 weeks of pregnancy). While that doesn’t cover every circumstance (and doesn’t go far enough for abortion rights absolutists), it does cover the vast majority of abortion cases and is politically more attentive to the sensitivities of centrist voters.

Trump, as noted above, would leave access to reproductive health to the states, which as a practical matter would ban abortion is more than half the country. Should Republicans win control of Congress, it would open the door to a national ban.

The affordability gap

Public opinion polls have consistently shown affordability has emerged as the leading health issue for many voters. This isn’t surprising given how half of all workers in private industry are now in high-deductible health plans.

The Harris campaign has sought to focus attention on medical debt. Cancelling the debt, as some have proposed, would cost an estimated $220 billion, although it’s unclear who would absorb those costs. Since much of that involves debts owed hospitals, the nation’s 5,000 hospitals could either raise prices to cover the unpaid bills or simply absorb the losses. I suspect most non-profit hospitals, which account for more than three-quarters of all hospital beds in the U.S., have already written off the losses as charitable care, something they’re obligated to provide to maintain their tax-exempt status with the Internal Revenue Service.

Still, I haven’t heard anything from either party about how to eliminate the affordability problem for families in high-deductible plans when they are hit with huge bills after experiencing a serious illness or accident. So I’ll offer my own solution, one I’ve written about before: No household should ever have to pay more than a set percentage of their income in any given year for all forms of health care (insurance premiums, drugs, doctors visits, hospital stays or any other service routinely covered by health insurance).

This cap on all out-of-pocket expenses could be set at say 4% of income or $2,000 for a household earning $50,000 a year; $4,000 for someone earning $100,000, etc. This new national insurance regulation could include a 1- or 2-year period for paying off this now capped but unexpected out-of-pocket expenses. This would renew interest among employers in setting up health savings accounts for lower-wage workers to pay off the unexpected bills.

This would, of course, raise insurance premiums to employers since it would socialize some of the costs that are currently being borne by households. But that is what health insurance — like car or house insurance — is supposed to accomplish: socializing unaffordable costs when they hit a small number of members of a much larger group.

It’s only by making private insurers adhere to this basic principle (without stinting on care or imposing large out-of-pocket expenses) that we can force the entire health care system to confront the central cause of the affordability crisis: The ridiculously high prices that insurers pay for almost every component of American health care.

As the late health care economist Uwe Reinhardt famous said, “It’s about the prices, stupid.” How to address high prices without resorting to price controls is a subject for another day.

I like the annual cap on out-of-pocket expenses (although I'm not sure health savings accounts would help--might just mean less coverage, higher premiums, etc.) And of course Uwe Reinhardt was exactly right about prices. But the reason the prices are so high is power. Prices only approach costs in a perfectly competitive market, where by definition NO participant has market power, there is total transparency, etc. In medicine, hospitals and insurers and now "health care systems" have immense power; patients and doctors have none, with predictable results. So I vote for price controls, which could be regulated just like utility prices used to be regulated (maybe still are) providing due process per the APA, instead of the RUC. We need Medicare-for-All (not Medicare Advantage, of course), financed by taxes on employers and workers. Since disease is now chronic and predictable, everyone at some point needs care, everything medically necessary should be covered, I'm not sure why we need private insurers to provide different 'plans'. Medicare would spread medical risk over the entire population. Today's Medicare was supposed to be just the first step, but then the New Deal ended, unexpectedly, in 1968.

CBO estimates 10-year cost of subsidies in the 300B+ range. The number of additional enrollees estimated to be 3.6M. Square those per capita costs for the incremental bump in lives covered? Where is all the money going?