Insulin update: Price cuts ... for now

With non-profits lining up to provide low-cost generics, Eli Lilly may have stolen a page from the John D. Rockefeller playbook

Last week’s decision by Eli Lilly to sharply reduce insulin prices is a direct challenge to the non-profit and government-run organizations rushing to create low-cost generic alternatives for a life-saving drug that is taken daily by more than 7 million Americans with diabetes.

Let me cut to the chase. This latest move by the Indianapolis-based drugmaker deserves close and ongoing scrutiny by antitrust officials at the Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Justice Department. The company, which along with Novo Nordisk and Sanofi control over 90% of the global insulin market, may be laying the groundwork for engaging in predatory pricing and marketing tactics with the idea of preventing non-profit producers from gaining a foothold in the market.

Eli Lilly’s price reductions were a response to the national uproar over the sky-high price of insulin, which soared sixfold over the past two decades. Responding to a crisis that led to an estimated one million diabetics self-rationing their medication, several non-profit organizations stepped forward to produce their own versions of synthetic insulin, which no longer is patent protected.

CivicaRx, which grew out of Intermountain Health in Utah and now includes several large health systems among its backers, next year plans to introduce a generic form of insulin that will sell for $30 a vial. California has earmarked $100 million to manufacture and purchase low-cost insulin for its residents.

Cheers for Lilly’s move

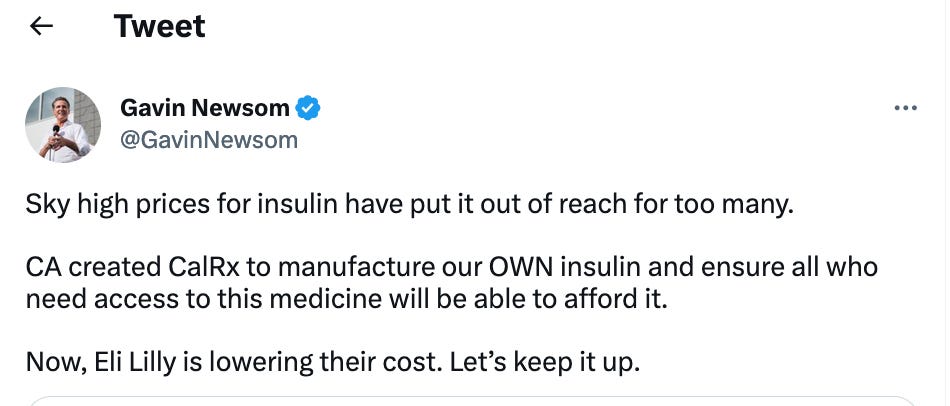

When the news of Lilly’s price cuts broke, Gov. Gavin Newsom tweeted: “CA created CalRx to manufacture our OWN insulin and ensure all who need access to this medicine will be able to afford it. Now, Eli Lilly is lowering their cost. Let's keep it up.” However, the state still hasn’t announced when it will have its own version or how much it will cost.

Eli Lilly, which introduced its first insulin product a century ago, promised that by October it will reduce the price of a 10-milliliter vial of the fast-acting Humalog to $66.40 from $274.70, a 76% decrease.

It also promised to reduce the price of Humulin, a long-acting daily version of insulin, to $44.61, a 70% decline. The company also plans to cut the price of its “authorized” generic version of Humalog to $25 a vial as early as this May.

The moves came in the wake of Congress including a provision in the Inflation Reduction Act that reduced the cost of insulin for Medicare beneficiaries to a maximum of $35 a month. The new law did not cover the private insurance market. Depending on the severity of their disease and weight, diabetics require anywhere from one to three vials of insulin per month.

Eli Lilly also announced it would expand its patient assistance program to keep out-of-pocket monthly costs within the $35 cap. Non-Medicare insurers, which are not covered by the IRA cap, typically include a co-pay in their coverage.

The moves by Eli Lilly were mostly well received. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) immediately sent letters to Novo Nordisk and Sanofi demanding they make similar cuts in the prices of their insulin products. “Insulin is not a new drug,” he wrote. “It was discovered 100 years ago by Canadian scientists who sold the patent rights of insulin for just $1 because they wanted to save lives, not make pharmaceutical executives extremely wealthy.”

Sanders’ rhetoric aside, we’re long past the time when that first version of insulin – harvested for human use from the pancreases of slain cattle – came to market. Today, all forms of the drug are made through genetic engineering.

Lilly introduced the first synthetic version in 1982. The first long-acting version received regulatory approval in 2000. Both are also well beyond their patent expiration dates.

Yet it wasn’t until the prices became exorbitant and standards for producing generic biosimilars became slightly less onerous that non-profits interested in offering low-cost generics jumped into the fray. The leading non-profit took Eli Lilly’s most recent move as a sign their strategy is working. “We have always believed that the market would respond to Civica’s pricing, and that is a good thing, said Allan Coukell, senior vice president for public policy. “Civica’s goal is market impact, not market share.”

Predatory pricing

But those pushing a non-profit manufacturing solution might want to take a close look at the granddaddy of major antitrust cases involving predatory pricing: the 1911 U.S. Supreme Court case that led to the breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil trust.

The high court found Rockefeller’s firm charged prices below the cost of production in over 100 markets where it faced competition in order to drive out its competitors. Standard Oil used the high prices it charged in markets it had already monopolized to underwrite the strategy. The scheme was aided by the anti-competitive practice of paying kickbacks to the railroads that hauled the oil, thus getting preferential access in most markets.

It seems to me there is a very real danger that Eli Lilly and the other Big Pharma companies producing insulin, assuming they follow suit, could pursue a similar strategy. Their goal would be to ensure that generic manufacturers never come to market with their own insulin products. Their rebate arrangements with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which are the equivalent of the railroads in the drug trade, can be easily manipulated to cement their lock on the market.

While that may benefit patients and payers for a while, it would set the stage for a bounce back in prices. As we’ve seen in recent years with many generic drugs when their prices are driven to extreme lows, producers without deep pockets exit the market or never enter. That allows the remaining Big Pharma players to begin hiking prices again since restarting production can be an expensive and time-consuming process.

That’s already a concern for some patient advocacy groups. “Additional competition and other accountability moves are still incredibly necessary because the companies can raise their list price again at any time,” Elizabeth Pfiester, founder of T1International, a diabetes patient advocacy group, told Kaiser Health News. “That’s why the government also needs to regulate insulin manufacturers to hold them accountable.”

Oversight needed

Using the nation’s antitrust laws would be the surest and fastest way to crack down on such anti-competitive behavior should it emerge. However, that will require a major shift in recent antitrust practice, which follows a principle laid down in 1986 by the Warren Burger high court decision in Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio. That 5-4 ruling stated “predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.”

Since then, “antitrust plaintiffs generally lost predatory pricing claims during the pre-trial motions phase of litigation, as lower courts invoked the Matsushita Court’s assertion that predatory pricing does not occur because it is irrational,” wrote University of California Irvine law professor Christopher R. Leslie in a 2018 article in the Southern California Law Review. Leslie’s article offered a systematic critique of a 1958 article in the Journal of Law and Economics by University of Chicago professor John S. McGee, one of the forerunners of the modern conservative legal movement. His frequently cited article succeeded in undermining the legal basis for antitrust enforcement in predatory pricing cases that had been established by the 1911 Standard Oil case.

McGee argued predatory pricing was theoretically impossible since any firm that exited because of the practice could just as quickly reenter the market when the remaining company, now a monopolist, raised prices to super-profitable levels. The idea that there might be barriers to entry – anyone familiar with the pharmaceutical industry knows there are enormous regulatory, scientific and manufacturing roadblocks to rapid re-entry – didn’t enter his thinking. Writing six decades later, critic Leslie called McGee’s article “a theoretical polemic masquerading as an empirical case study.”

Yet McGee’s reasoning is now the law of the land. Given the current make-up of the high court, FTC Commissioner Lina Khan, the Biden administration appointee who has reinvigorated antitrust enforcement, faces an uphill battle should Eli Lilly and the other Big Pharma insulin producers follow in John D. Rockefeller’s footsteps.

Thanks for this history. Hopefully, the currrent FTC is aware of it. Unfortunately, the 1986 Matsushita decision came just a few years after the history you recount and the current court no doubt would endorse its false logic.

Merrill, you nailed it again. After decades of price gouging diabetic Americans, there’s no altruism in the Eli Lilly move. Rather, it’s a response to market pressures resulting from the $35/month cap for Medicare beneficiaries, California’s move to manufacture its own insulin, nonprofit Civica’s market entry and billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban’s plan to sell low-cost insulin. Fortunately, the circumstances today are different from the Standard Oil days - given the mix of interests involved in fighting high insulin costs (federal and state governments, major health systems, commercial insurers and billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban), the likelihood of Lilly pulling off predatory pricing tactics to drive competitors from the market has a far lower probability of success. Nonetheless, we must remain vigilant - Big Pharma will always place profits above patients.