Medicaid in GOP's crosshairs

Re-enrollment, work requirements threaten COVID-era expansion. Rules just proposed by CMS will help bolster the program.

The pandemic turned Medicaid into the nation’s largest health insurer. The program, which provides health insurance for the poor, now covers over 85 million people or one in every four Americans. They include the impoverished elderly, 41% of all childbirths and about 11 million disabled, many with Downs syndrome and other intellectual and developmental disabilities. About 20 million individuals joined Medicaid during the COVID-19 emergency.

But that expansion is about to move into reverse. Last month’s end of the public health emergency automatically restarts the program’s annual re-enrollment process, which had been on hiatus since 2020.

Those annual re-determinations, which look mostly at income eligibility, invariably require submission of extensive paperwork. The Kaiser Family Foundation last week estimated as many as 17 million people could lose coverage by the end of this year, “including some who are no longer eligible and others who are still eligible but face administrative barriers to renewal.”

Health care organizations across the country are gearing up to re-enroll as many people as possible. They include hospitals with a large Medicaid clientele; federally qualified health centers that serve the poor; and private insurance companies, which now control the bulk of Medicaid spending (about 70% of Medicaid enrollees are now covered by insurer-run managed care organizations or MCOs, which is higher than the 50% of Medicare beneficiaries now enrolled in private Medicare Advantage plans). Most have created in-house programs to facilitate the process.

No work? No health care for you

Meanwhile, Republicans in Congress are fixated on increasing the ranks of the uninsured. House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy made Medicaid work requirements a key part of the budget cuts that the GOP insists must be part of any agreement to raise the federal debt ceiling, which must be lifted sometime next month or the nation’s economy will be thrown into chaos.

The Congressional Budget Office last week estimated work requirements, if implemented nationwide, would deny about 600,000 people access to the program. Studies of Arkansas, the only state to set up work requirements, showed the program was a total bust – unless your goal was to throw tens of thousands of people off the rolls and make low-wage workers’ lives more difficult. The program had a minuscule impact on overall employment in the state.

That didn’t stop 13 Republican-run states from applying for and receiving similar work requirement waivers during the Trump administration. They were immediately rescinded by the Biden administration. The move was recently upheld by the courts as a violation of the program’s purpose of providing health insurance for the poor, which includes those who work for such low wages that they still qualify.

As a KFF brief noted last month:

“Prior to the pandemic, the majority (63%) of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees who did not qualify based on a disability were already working full- or part-time. Most who were not working would likely meet exemptions from work requirement policies (e.g., had an illness or disability or were attending school), leaving just 7% of these enrollees to whom work requirement policies could be directed.”

And who were those 7%? Although not officially designated as disabled, most suffer from conditions that make it almost impossible for them to find jobs: homelessness, depression, substance abuse and other behavioral health disorders. In other words, these are people who need health care services to return to the work force – not removal from the one program that would give them access to that help.

A proposal to increase home health aide pay

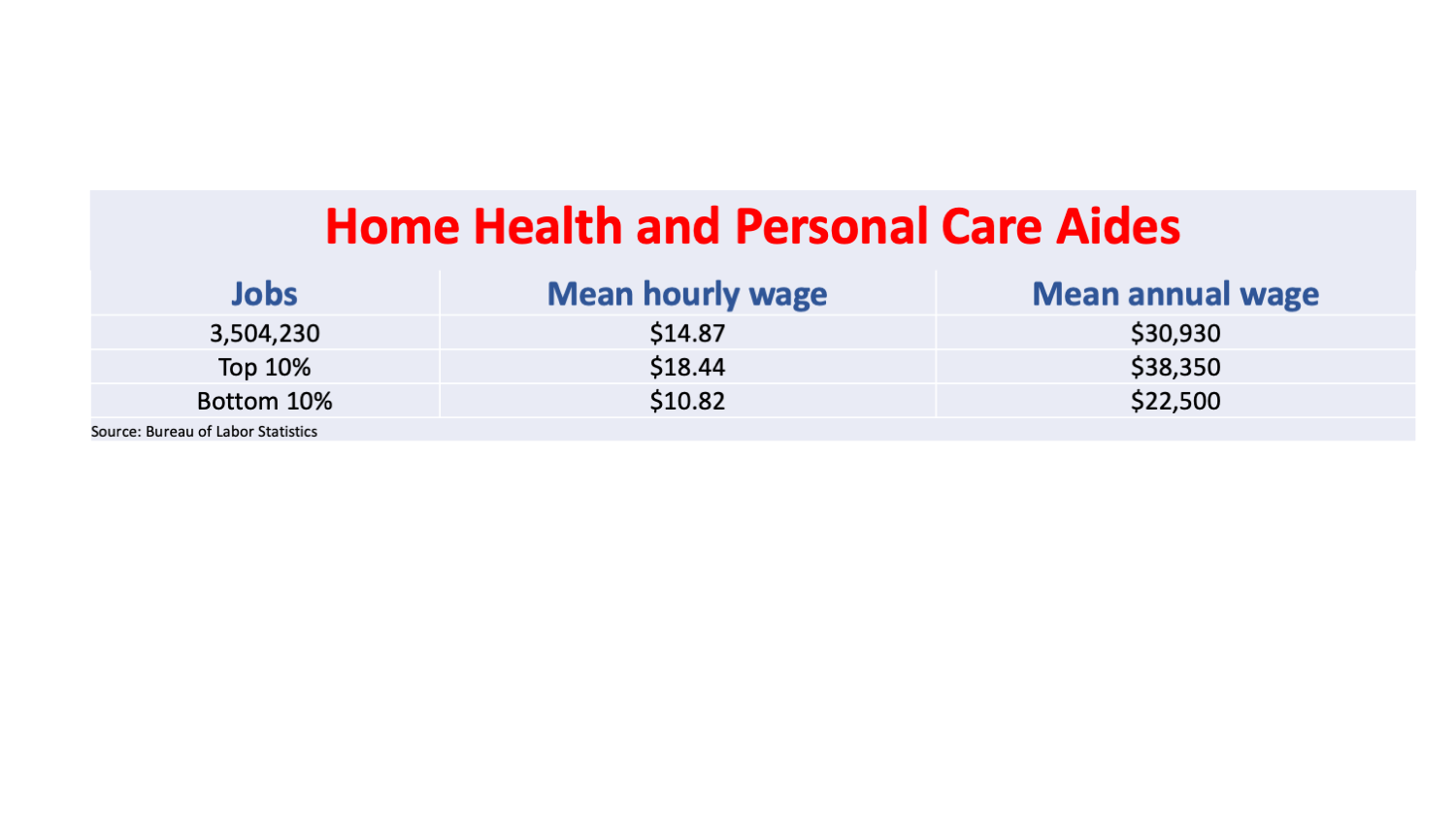

And how much would work requirements save by throwing people off the rolls, anyway? The CBO estimated $109 billion over ten years. I wonder how that compares to the proposed rules the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued last week, which would require home care providers spend at least 80% of Medicaid reimbursement for home health aide services on direct compensation for workers (with the other 20% a maximum for administration, sales and other non-employee costs). It also would require states publish the average hourly rate for those workers.

Home and community-based services (which include rents for group homes for the intellectually and developmentally disabled as well as services provided within those homes) is one of the fastest growing components within Medicaid. Families, caregivers and most state Medicaid agencies want to keep disabled individuals out of nursing homes. Medicaid payments for home and community-based services reached a stunning $163 billion in 2020, according to KFF.

Indeed, the sector grew so fast over the past decade that it became a ripe target for private equity funds, which has drawn criticism from the consumer- and worker-oriented advocates like the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, whose studies show private equity firms siphon off resources while allowing quality, working conditions and pay to deteriorate. A team of investigative reporters from the now-defunct BuzzFeed News took an in-depth look at just one of those takeovers – KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.)’s 2019 purchase of BrightSpring Health Services, one of the nation’s largest group home operators with over 600 residential facilities in almost every state.

After reviewing hundreds of state inspection records and conducting 170 interviews with regulators, client families and current and former workers, the investigative team concluded that “again and again residents (were) consigned to live in squalor, denied basic medical care, or all but abandoned… BrightSpring executives in many cases kept wages lower than those at competing facilities or Walmarts, despite pleas from local managers that they were unable to safely staff the homes.”

KKR “vehemently disagreed” with the report and BrightSpring, which has over 37,000 employees and cares for 330,000 patients daily in 125,000 group homes, called it “inaccurate, misleading, and fundamentally flawed.”

But as often happens with private equity takeovers, the truth (or at least some of it) eventually comes out. KKR briefly sought to take BrightSpring public in October 2021 through an initial public stock offering. Its Securities and Exchange Commission filing revealed just 74% of its $1.9 billion in direct service revenue in 2020 was spent on the cost of those services.

The CMS proposed rule that would bring that level up to 80% will generate (admittedly, my back-of-the-envelope estimate) an additional $116 million a year for increased worker pay at BrightSpring. Or, to put that in perspective, that’s an additional $3,152 for every worker on its payroll – skilled and semi-skilled, management and line employee, whether they are in its home health division or its larger products division (revenue-wise, at least), which sells pharmaceuticals to the residents in its group homes.

That would be a welcome increase for workers, disproportionately minority, many of them immigrants, 16% of whom lack health insurance and 41% of whom are so poor that must rely on public coverage, most commonly Medicaid, according to PHI, a non-profit research organization that promotes “quality care through quality jobs.”

The wage standard was just two of the dozens of provisions in two rules weighing in at nearly a thousand pages, which will be open for comment for 60 days after its publication (slated for May 3). Others include requiring states to publicly post payment rates for the 30% of beneficiaries still in fee-for-service Medicaid; a comparison of those rates to the rates paid by Medicare; and require insurer-run MCOs to post the rates they pay providers, which currently go unreported.

That information should proven enlightening for many Medicaid patient advocates, and help explain why so many providers have so little interest in serving our neediest and least healthy citizens.