The growing crisis in maternity care

Maternal mortality is rising; infant mortality remains outrageously high. Does anyone in the anti-abortion movement care?

I spent time on the National Right to Life Committee’s website today. I wanted to peruse the antiabortion group’s policy prescriptions for reversing America’s disturbingly high moms-in-waiting and new moms death rate, which has grown much worse in recent years.

Not a word. Nor did the group have anything to say about the U.S. having the worst infant mortality rate among advanced industrial economies or the paltry level of financial, nutrition, and social service support we give young families.

You would think in this election season that Republican lawmakers in thrall to the right-to-life movement would offer something considered family friendly, especially since political survival for at least some of them will depend on deflecting the majority’s anger about the high court’s denying every woman’s right to privacy and personal choice.

Right on cue, in September Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) introduced his “Providing for Life” act, which would give paid family leave to new working mothers. But he would force them to draw down their future Social Security benefits to pay for it. The bill would also force new mothers on food stamps to cooperate with state officials going after non-custodial parents for child support payments or risk losing their benefits. So it goes for kinder and gentler Republicanism.

While the Rubio bill would create a “clearing house” for listing the available resources to pregnant and young mothers, it provided no money for additional programs beyond grants for mentoring young mothers, an expansion of the earned income tax credit and extending supplemental nutrition benefits for women, infants and children (WIC) an extra year to age two. While latter two measures are long overdue, it remains far short of the major expansion of financial and social support for young families called for by advocates, which includes employer-paid family leave, childcare support and universal pre-K education. Only some of that was included in the Biden administration’s original Build Back Better bill.

The woeful state of U.S. support for young families was summed up in an article in the Atlantic earlier this year. “On so many measures of family hardship, young children and their parents in the U.S. suffer more than their counterparts in other high-income nations.”

Babies are more likely to die and children are more likely to grow up in poverty. The U.S. is the only rich country in the world without national paid family leave. And while other wealthy countries spend an average of $14,000 each year per child on early-childhood care, the U.S. spends a miserly $500.

Isn’t it time we begin demanding that conservative lawmakers and right-to-life zealots support women while they are pregnant and after their children are born?

A sorry record

Let’s start with the health of mothers, where the U.S. record, already worst among advanced industrialized nations, is growing more dire. In 2020, around 900 women died of pregnancy-related causes, up 31 percent from 2018. The U.S. rate of 23.8 pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births was more than twice that of other advanced economies.

The Black maternal death rate is a scandal, well over twice the national rate. Yet white mothers are not immune. They also suffer deaths during or just after pregnancy at a rate that’s twice the OECD average.

It’s important to remember that an estimated two-thirds of maternal deaths are entirely preventable when mothers are given adequate pre- and post-natal care, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The following chart speaks volumes about the ability of our health care system to serve women at this vulnerable time of life.

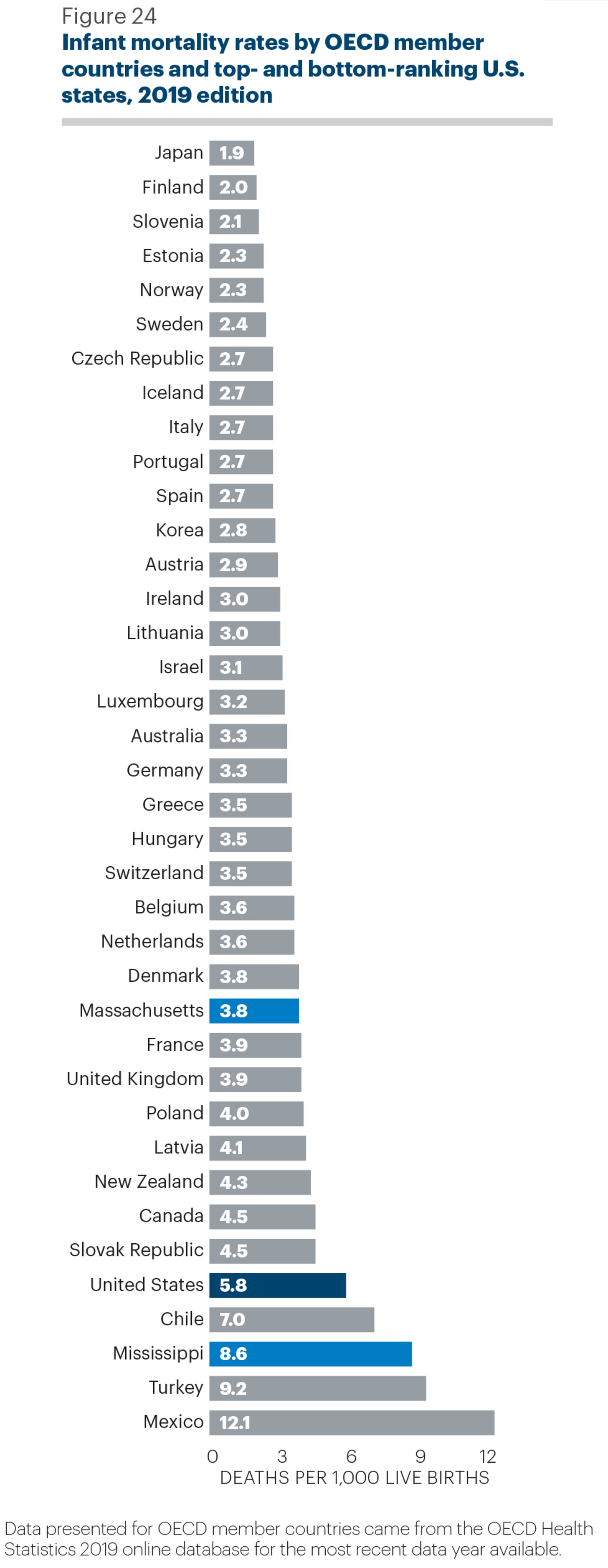

As has been documented many times, the U.S. is among the worst performers in bringing newborns into the world alive and making sure they stay alive during their first year of life. Our infant mortality rate stands at fourth highest in the OECD (trailing only Chile, Turkey and Mexico) and now stands at twice the group average.

Life and death in a desert

One reason for our sky-high infant mortality rate is that there are wide disparities in access to maternal and neonate care across the U.S. Without access to acequate pre-natal care, young mothers are more likely to deliver pre-term babies or babies with low or very-low birth weights, which increases sickness and death among this very young cohort.

The above chart documents how the best performing state (Massachusetts) on infant mortality is not much different from northern European countries, while the worst performing state (Mississippi) is closer to the levels seen in Turkey and Mexico. But the variation is not just between states.

A recent report from the March of Dimes highlighted how more than one-third of all counties in the U.S., disproportionately rural and in the Deep South and Midwest, are considered maternity care deserts. They have no birthing centers, obstetric hospitals, or physicians trained to take care of pregnant women, new moms and their babies. Those deserts are home to seven million women of childbearing age, who give birth to about 500,000 or one in seven babies born in the U.S. each year.

Why has the health care system abandoned these areas? Here’s one possible reason: There’s a growing shortage of physicians available to meet their needs.

According to a March 2021 report from the Health Resources and Services Administration, fully trained OB-GYNs available to serve expectant and young moms is expected to fall 7 percent between now and 2030, largely due to retirements. Meanwhile, demand for OB-GYNs is expected to grow by 4 percent. That will leave a shortfall of nearly 5,000 OB-GYNs by the end of the decade.

Of course, the government could make up for the shortfall by increasing the number of residency slots for medical school graduates looking to become OB-GYN and family medicine specialists. But the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization will only make that task more difficult.

I will turn to that subject in my next post later this week.

An important column on an important matter dealing with medical priorities. It reminded me that California is providing $12 billion for stem cell research as the result of a ballot initiative that locks in the cash for those worthy pursuits without allowing the public to weigh in on what they think are the most important health care priorities in California.

I am fond of ambitious efforts to explore the unknown and develop miracle therapies. But I am also fond of attacking immediate health care issues with the possibility of at least saving lives within shorter time frames. Is it really possible to do both within the constraints of limited dollars and a limited will on the part of our political leadership to tackle them both?

You all can read more about the Golden State's research program on the California Stem Cell Report. https://david293.substack.com/

Thanks for highlighting a life and death issue Americans are comfortable ignoring. It is clear women and children are not a priority and America is not willing to invest in a society that assures the health of our women and children. The remedies are inexpensive and readily available if we cared.

This medical services industry dedicated to hyper-capitalism has deemed obstetrical and pediatric services as loss leaders and does not invest in training health practitioners, or prevention and health education required by the basic needs of society for reproductive health. MD’s have fought for the monopoly to deliver babies yet have limited the supply of trained physicians because OBGYN, Family Medicine, and Pediatrics are all low reimbursement specialties, with few high reimbursement procedures (tho’ it is worth looking at excessive US C-section rates in light of economic incentives vs medical necessity/evidence based practice).

A community based comprehensive reproductive and infant health delivery system based on midwives and doulas(with MDs only co-managing high risk pregnancies) with a focus on home or birthing center deliveries would increase access, decrease cost, and improve outcomes. A focus on prevention and health education based in communities and designed to meet a population’s health needs would include sex education, contraception, and early pregnancy detection. A humane system would empower women to make their own choices and maximize planned pregnancies. Addressing the larger social determinants of maternal and infant health would address access to childcare, nutritious food, medical and family leave, housing, and basic social supports.

These are all standard practices in countries with lower maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. These changes would gore the oxen of powerful political and economic forces with a strong attachment to maintaining the status quo. They have no political or economic advocacy. In this reality, real change is impossible. Americans choose to condemn women and children to needless suffering and death. It has become normalized and acceptable cost of doing business.