Will health care return to normal? Should it?

It's not to soon to start thinking about what a better system might look like after the pandemic

It is impossible to predict when the nation’s health care needs will return to normal or what a post-pandemic new normal might look like. Much remains unknown.

Will future variants look like Omicron, less severe for all but the unvaccinated and vulnerable, thus turning COVID into a flu-like disease? Or will a new, more virulent strain emerge that prolongs the pandemic and exacerbates the nation’s divisions on how to deal with it?

Will the sharp drop in preventive and routine care visits over the past two years lead to an uptick in non-COVID deaths and disease?

Will there be surge in new health care spending as physicians and hospitals begin treating people farther along in their diseases? Or will we discover that a lot of routine care wasn’t necessary?

As the economy recovers, will health care spending, which surged to 19.7% of the total gross domestic product in 2020, drop back into the 17-18% range experienced over the past decade? Or will unmet medical needs and the ongoing pandemic combine with a faltering economy to make the current high levels of spending permanent?

Here are a few facts to consider in thinking about those questions. Even if COVID turns into a less deadly but endemic disease, it will remain a major public health concern. Influenza kills 40,000 to 80,000 Americans every year, depending on the virulence of the annual variant. That makes it the ninth leading cause of death.

The pandemic revealed the U.S. is psychologically ill-prepared for dealing with infectious diseases that require a disciplined, society-wide response to mount an effective defense. We are likely to see more such outbreaks in the years ahead. In an era of global warming, we can no longer afford to think of pandemics as once-in-a-century events. How much will it cost this nation to prepare for the next one when it knows a third of the population will resist basic public health measures? Surely that will cost more, not less.

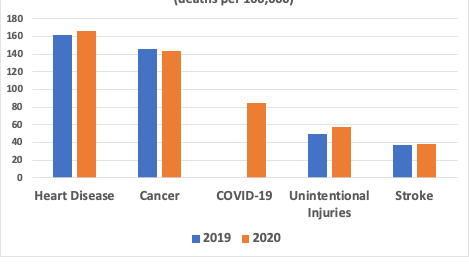

COVID isn’t the only health problem this nation faces. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest report on mortality and longevity released in December showed longevity fell 1.8 years to 77 in 2020 from 2019, almost entirely due to COVID, which became the third leading cause of death.

However, the death rate from heart disease, the leading cause of death, rose 4.1% in 2020 from 2019. So did the mortality rates for unintentional injuries (up 16.8%); stroke (up 4.9%); Alzheimer’s (up 8.7%); diabetes (up 14.8%); and influenza and pneumonia (up 5.7%). The only mortality rate among the five leading causes of death that fell was cancer. The second leading cause of death was down a scant 1.4%.

These grim statistics continue trends that saw U.S. longevity falling in three of the four years prior to COVID. Before the pandemic, public health officials and health care practitioners blamed what Princeton University economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case called deaths of despair: suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol-related liver disease, which are highly concentrated among the nation’s non-college educated population. None of those issues has gone away.

The nation also suffers from an uncontrolled obesity epidemic. It is a major contributor to rising rates of diabetes, high blood pressure, mental health disorders and many forms of cancer.

And it was generally conceded the nation’s behavioral health and substance abuse treatment programs were in shambles. They suffered even more neglect during the pandemic.

Social stressors

Prior to the pandemic, there was also renewed attention to what health care practitioners call the social determinants of health – the poor housing, inadequate nutrition and the low wages that increase disability and severe disease in the bottom half of the nation’s income distribution. The protests triggered by George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis underlined the endemic racism in our society, a social stressor that, along with the maldistribution of health care resources, is a major contributor to lagging health status in the nation’s African American community.

For all those reasons, there’s good reason to think that the demands on the health care system will remain high and continue to grow once we move beyond COVID.

It’s hard not to conclude that the nation’s failure to deal effectively with the COVID pandemic is generating a lot of pent-up demand for health care services. And our myriad societal dysfunctions, rooted in unprecedented levels of income and wealth inequality and growing social discord, show no signs of abating.

But do we really need to spend more on health care? The U.S. remains the outlier in terms of the level of societal resources that it devotes to treating the sick – nearly half again as much on a per capita basis as any other country on earth. There is plenty of money in the system to address all our needs – if only it were better targeted.

What we need to address, even as we grapple with how to emerge from this seemingly never-ending pandemic, is how to create a better delivery system — one that devotes more of its resources to promoting better health. And we need a better system for meeting basic human needs. That will require far-reaching payment reform – the subject to which I’ll turn to tomorrow.