The All-Payer Pricing Alternative

Public option proponents face huge political hurdles; there is another way to achieve many of the same goals

The media has already written the epitaph for major health insurance reform legislation during the current session of Congress. While the Biden administration has expressed support for a publicly-owned insurance plan to compete with private insurers on the exchanges, key Democratic Party leaders are in no hurry to take up that agenda.

On the same day the president released his budget message, Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA), chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, and Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, gave insurers, providers and the public over two months to provide “guidance” on a public option bill their committees plan to write. As the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Larry Levitt astutely noted in a JAMA Forum commentary, “the promise of an aggressive campaign against both Medicare-for-all and a public option by the health care industry may have spooked moderate Democrats.”

A few states under Democratic Party control are moving to fill the void. Nevada’s legislature recently followed in Washington State’s footsteps to pass a public option bill, which its governor is expected to sign. Colorado is considering similar legislation.

There is precedent for states acting first on major health insurance reforms. The Massachusetts plan passed in 2006 became the basis for the U.S. adopting Obamacare four years later. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously said in 1932, "a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country."

But is the public option the best reform to pursue at the state level if the goals are to achieve universal coverage and more affordable insurance premiums? To buy off vigorous opposition from health care providers, Washington state’s public option, called Cascade Care, had to set prices for hospital and physician services at an average of 160% of Medicare’s prices – in other words, not much different than the prices private insurers pay. As a result, only 15% of the 222,731 state residents who purchased plans on the exchanges for 2021 bought a Cascade Care plan, which was the low-cost option in just 8 of the state’s 39 counties.

Moreover, the Washington state experiment isn’t government-run plan like Medicare or Medicaid. It’s a limited form of rate regulation. The legislation set benefit standards and payment rates for an additional plan that private insurers must sell and administer if they want to participate on the exchange.

This is a far cry from the public option as originally conceived by Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker as a steppingstone to a single-payer system or Medicare for All. He called his latest formulation, offered three years ago as single-payer advocates gained ground within the Democratic Party, Medicare Part E (for everyone) — a government-run plan that would automatically enroll everyone without private insurance and require employers who don’t provide coverage to contribute to financing the plan.

In addition to providing universal coverage in one fell swoop, Medicare Part E “would also begin to deliver on Medicare for All’s second promise – lower prices,” he wrote. “More people would be covered by Medicare, which would mean more services financed at Medicare rates.” Private plans would be forced to negotiate lower prices “so their customers wouldn’t switch to Part E.”

Washington state’s experience reveals the political problem with that approach. Health care providers will attack any public plan that pays Medicare rates because it entails large cuts in their revenue. Small businesses that don’t provide health insurance will oppose a public option as vigorously as Obamacare (recall that the National Federation of Independent Businesses mounted the first Supreme Court challenge to the 2010 law) since they will have to pay new taxes to cover the previously uninsured. And it doesn’t win many friends among responsible businesses that already provide health insurance for 160 million Americans, who will accurately perceive the plan as the slippery slope toward ending the benefit that helps them retain employees.

A public option plan that pays Medicare rates also imposes enormous transition costs on the existing system. To the extent insurers fail to negotiate lower rates because of the presence of a public plan (the work of Hacker’s colleague Zach Cooper at Yale suggests increased monopolization among providers will prevent that from happening), employers will be forced to pay higher rates to make up the difference. To the extent they can negotiate lower rates, hospitals and physician practices will be forced to lower salaries for doctors, nurses and other personnel, which accounts for over half of all health care spending.

“Even Medicare for All purists understand a staged approach might be necessary,” Hacker noted in his article. But he also admits that a public option could lead the U.S. either toward single-payer or toward a German-style system, where private insurers continue to play a major role. He even has kind words to say for Medicare Advantage, the insurer-run portion of the program that has captured 43% of the senior program.

Either way, to pass a public option, a broad political coalition must be built to support it – one that includes providers, their employees, employers, and perhaps even insurers. The architects of the Affordable Care Act understood that political reality and succeeded in building such a coalition. It also must include a gradual path to bringing U.S. health care costs down to international norms – not the abrupt drop in revenue that a substantial shift toward Medicare payment rates represents.

What follows is my attempt to outline what might be an achievable alternative to accomplish many of the same goals.

What health care and airlines have in common

Let’s start with some basics. The U.S. has the most complicated medical payment system in the world. Providers (hospitals; doctors; clinics; labs; drug, medical device and machinery manufacturers; etc. etc.) primarily rely on fee-for-service payment, where they receive a set or negotiated price for each unit of service or product delivered.

But every provider charges multiple prices for the same service depending on who pays the bill. Government programs – Medicare and Medicaid – pay government-set prices that are less than the actual cost of delivering care. Private insurers and self-pay private employers pay significantly higher negotiated prices – anywhere from 120% to 340% higher depending on the service, according to this recent paper by Matthew Fiedler of the Brookings Institution. Moreover, each insurer or private payer negotiates their own rates with providers, which means a hospital or physician practice may charge a dozen or more different prices for the same service.

Hospital or physician practice administrators’ main goal is raising sufficient revenue to meet their annual budgets. They accomplish that through a blend of the higher prices paid by their privately insured patients (about half the population) and the lower prices paid by their publicly-financed patients (the other half). When Medicare holds down prices through administrative fiat or Congress imposes cuts, providers – especially those that are high prestige or are dominant in their markets – demand and usually win higher negotiated rates from insurers and the private employers they represent. It’s a hidden tax on their workers’ wages, which, as any economist will tell you, includes the cost of health benefits.

Single payer advocates and other progressives point to Medicare and Medicaid’s success in holding down overall costs as proof of the superiority of public payment systems. What they overlook is the extent to which that success has come at the cost of higher rates for the privately insured. To deal with this cross-subsidization, many private employers in recent years have begun shifting a growing share of those rising charges onto the backs of their workers through higher deductibles, higher co-insurance premiums and higher co-pays, which amount to another tax on workers’ wages. This is the number one reason rising out-of-pocket costs and not the presence of 10% of the population remaining uninsured has become the number one political concern of most Americans when it comes to health care. It’s also a major factor behind wage stagnation since money that would otherwise go into paychecks goes instead into paying higher health care bills.

This Gordian knot of cross-subsidization explains why providers have joined forces with private insurers to oppose a public option. A public option at Medicare rates would rapidly become the dominant insurer in the individual market. Its presence would encourage many employers that currently offer health insurance to immediately drop their plans. That, in turn, would lead to rapidly rising rates for the shrinking number of privately insured plans. The ensuing death spiral would eventually drag down even the largest employer-based plans. Numerous hospitals and physician practices across the country would face financial insolvency if forced to accept Medicare rates for the bulk of their paying patients.

The only way to avoid this scenario is to create a public option that pays a blended rate that reflects the actual cost of care. Washington state’s 160% average may be too high – the public plan in its first iteration didn’t get many customers – but it probably isn’t too far off the mark in terms of assuring provider solvency.

But, as I pointed out earlier, Washington’s experiment didn’t create a public plan. It required insurers to offer at least one plan that used the state-imposed rate structure. “It’s rate setting,” said Chelene Whiteaker, senior vice president of government affairs for the Washington State Hospital Association. “They’re setting rates in the individual commercial market to offset the low reimbursement for Medicare and Medicaid. We’re fundamentally worried about the shift to this public option plan, which still has rates that will undermine the financial viability of hospitals.”

Why not all-payer pricing?

Only one state in the nation avoids cross-subsidization pricing and, as a result, can offer insurance plans to uninsured individuals and families on its exchange that are among the least costly in the nation.

Since 1974, Maryland has maintained a price-setting regulatory authority for health services that is similar in function to the commissions in every state that regulate natural gas and electricity prices. In 1977, the state and its Health Services Cost Review Commission was one of five that received federal government permission to set up a hospital pricing system where all payers – including Medicare and Medicaid – pay the same rate for the same service at any given hospital in the state.

Different hospitals are allowed to charge different rates based on their historic baselines. But individual hospitals cannot charge different patients different rates based on the insurance card they carry. It’s called all-payer pricing. Maryland is the only state that has kept the system.

The federal waiver is key to setting up all-payer pricing since it requires additional taxpayer dollars to increase the prices paid by Medicare and Medicaid to the regulated rates. Prices paid by private insurers for their customers fall commensurately.

A recent analysis of Maryland’s system by RTI International, which looked at fiscal years 2011 to 2018, revealed for the first time the scale of the cost-shifting that takes place under hospitals’ variable pricing regimes in other states. “Depending on the year and basis for comparison, Medicare payment rates for inpatient rates were 33 to 44 percent higher under Maryland’s all-payer rate-setting system than under the IPPS (Medicare’s regular fee-for-service fee schedule),” the report said. “Depending on the year, commercial insurer payment rates for inpatient admissions were 11 to 15 percent lower in Maryland than in a matched comparison group (drawn from hospital private insurance charges in other states).”

In the 1980s, the new system quickly lowered the state’s overall hospital spending, taking Maryland from among the highest cost states in the country to about the national average. But it got stuck there because all-payer pricing failed to control utilization. “Many hospitals responded to fixed prices by increasing the volume of services offered,” according to a Milbank Memorial Fund issue brief by Duke University researchers Mark Japinga and Dr. Mark McClellan, the former head of CMS.

So, to eliminate any incentive for unnecessary utilization, Maryland in 2014 applied for and received an adjusted federal waiver that allows state regulators to impose global budgets on each of the state’s hospitals. Those budgets are increased each year based on inflation, changes in population and other factors. Hospitals have the authority to adjust prices up or down throughout the year so the hospital is assured of receiving total payments that are close to their global budget (see this GoozNews article for how that worked during the pandemic when non-COVID hospital use fell dramatically).

The first five years under global budgeting resulted in 2.8 percent lower spending on Maryland’s Medicare beneficiaries compared to other states, the Duke researchers wrote, saving the taxpayers nearly $1 billion. More than 80 percent of the savings came from reduced hospital expenditures.

So to sum up: Maryland’s all-payer pricing system increased federal spending but allowed commercial insurers to lower premiums by double digit rates. When coupled with a global budgeting for hospitals, all-payer pricing slowed the growth of health care spending to a pace significantly slower than the overall Medicare program.

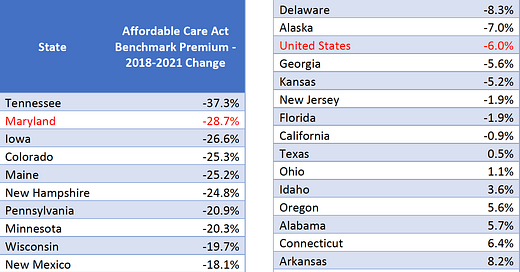

Pricing for private plans sold on Maryland’s Obamacare exchange reflect the positive results from its all-payer/global-budgeting approach. Benchmark premiums nationwide have fallen by a total of 6% over the last three years, according to data compiled by the Kaiser Family Foundation. But Maryland’s rates have fallen by 29%, second most among all states, leaving its benchmark premium 23% below the national average compared to being slightly higher in 2018.

Given the all-payer system doesn’t apply to physician services, drugs and other health care services, it’s hard not to conclude global budgeting tied to common prices in the hospital sector was responsible for much of that decline. Given those other sectors account for two-thirds of all health care spending, there’s good reason to think, “the next phase of Maryland’s model will more explicitly address nonhospital costs and create a fresh set of incentives for physicians to support value-based care.” The authors of that observation in JAMA Internal Medicine included Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, the former secretary of health in Maryland, and Joe Antos, a conservative scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who sits on the HSCRC board.

The benefits

Elected leaders in states considering a local public option to achieve universal coverage at affordable rates might want to consider applying for a federal waiver that would allow them to set up their own version of Maryland’s all-payer/global budgeting system. Single-payer and public option advocates should also consider throwing their growing political clout behind a reform that has the potential to achieve many of their most cherished goals.

Here are the arguments. All-payer/global budgeting will:

Sharply reduce administrative waste by eliminating the multiple pricing schedules and billing systems inside hospitals and insurance companies;

Lower premiums for employer group plans and for individual plans sold on the exchanges; and

Incentivize hospitals to compete on efficiency, quality, service, safety and outcomes. In competitive markets, a single price for all services encourages price competition; in highly concentrated or sole source hospital markets, commission oversight provides a mechanism for reviewing outlier prices and makes moot antitrust efforts to stop consolidation in the name of fostering price competition that only applies to the privately-insured.

All-payer/global budgeting also has the potential to build a winning political coalition because it can:

Win political support from the hospital sector because it gradually achieves the goal of lower overall health care spending through slower growth in the global budget, not an immediate reduction in revenue;

Win political support from the insurance industry because it preserves its role in the system;

Win political support from the business community because it leads to an immediate and dramatic drop in their health care coverage costs and predictable growth rates going forward; and

Win political support from already insured Americans because it doesn’t tamper with their existing plans, immediately reduces their co-premiums, and, depending on how individual employers respond to the change, reduces their upfront deductibles and co-pays for individual services.

Finally, global budgeting begins the process of educating provider organizations that are addicted to constant revenue growth under fee-for-service medicine on how to take financial responsibility for all patients under their care – what health policy wonks call population health management. While Maryland’s current global budgets rely on price adjustments to traditional FFS payment, a next refinement in the system could be switching to monthly or annual payments for every covered life, which will free up health care system resources to invest in promoting better health, not just curing sickness.

“Those of us who have drank the Kool-aid are deploying the resources into patient-centered medical homes, behavioral health, sexual assault forensic examination programs,”said Dr. John Chessare, the pediatrician who is now CEO of Greater Baltimore Medical Center. “We’re spending money in the outpatient area to drive better value.”